Columnist Joe Banks of Vice met with Tom McClean at his home in Scotland and wrote a piercing essay about this amazing man. We're publishing an abridged version of it.

I'm standing by Loch Nevis Lake in West Highland staring at a 60-foot sperm whale. Its huge tail rises up against the backdrop of the nearby mountains.

His maker, Tom McClean, is standing next to me. We are in the middle «of an outdoor adventure» he created for himself on the desert shore of Lake Loch Nevis forty years ago. Since then, adventure has been an integral part of his life. An extraordinary boat is just one of his last attempts to turn excess imagination into something real.

«I've always been an adventurer," admits McClean. - He was obsessed with original ideas. I've tried my hand here and there». Most of the original ideas of a 73-year-old Scotsman were related to the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1969, while serving in SAS, he was the first man to cross the North Atlantic by himself in a rowboat. He travelled more than 2,000 miles, experiencing the monstrous power of cold storms with house-size waves and boat overturning in 71 days. He then crossed the Atlantic four more times alone, using boats of varying degrees of eccentricity. In 1982 he set a record with the transatlantic crossing of the smallest boat, the 9.9 foot Giltspur.

In 1985 he spent 40 days alone on Rockall, a piece of bare granite sticking out of the Atlantic Ocean a couple hundred miles west of the Hebrides. It was an independent (and largely barren) attempt to support British territorial claims to ownership of the tiny island, the ocean floor around which hides huge oil and gas reserves.

A few years later, at the age of 44, McClean crossed the Atlantic once again in a rowboat, this time to set a record for the fastest time.

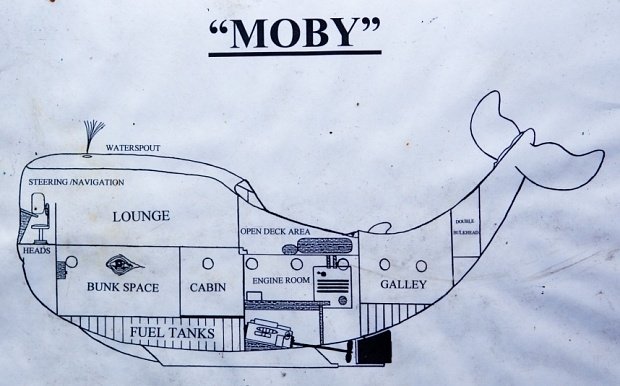

His latest project is a 65-tonne Moby boat in the shape of a sperm whale, complete with painted eyes and mouth, and an air vent from which a water fountain periodically rises. He is, of course, going to make a transatlantic transition on it.

«I put a lot, a lot of effort into it," said McClean. - A lot of people have a big blue dream, and of course they run out of money and it all comes out and stops. But we kept going. All we want now is for someone to find a good use»for it.

The idea of a whale boat appeared in the mid 90's when McClean returned from another of his travels. «Moby» was his nickname in the army, earned for his love of ranting.

Moby was being worked on at the construction site. «Why go to the shipyard if you're asked for 10 times the money there?» - Carelessly abandons McClean. It took him twenty years and about £100,000 to build a Moby.

After a successful first test drive around the British coast in the late 1990s, Moby remained broke in Highland.

«You no longer have dirty old diesel engines knocking around. You get rid of them, and the whale boat becomes an example to everyone. I really like the idea of bringing the company into the project and fighting to save the planet and do good»," says the creator of Moby. He hopes an NGO like Greenpeace, or a business specialising in renewable energy, will support the project.

It's amazing that McClean hasn't yet become a nationally significant figure in Britain, honoring sailors and explorers. In terms of his recklessness, his achievements seem to be comparable to those of Sir Ranulf Faines, a record-breaker in endurance.

During a tour of Moby McClean climbs up the whale tail of a boat. The small stocky figure - only 5.6 feet in it - but gives the impression of enormous physical strength and vital energy. He's 73, but he longs for his next adventure with as much strength as the young can get.

When we sit in the living room of a stone cottage he's built with his own hands, I ask him how he found the strength to go through all the ordeals he met on his way.

«This is not the case when you clench your teeth and say: I will not give up, this is something in your body. It's something in your whole being. I don't think you can train that ability. I got it from an orphanage in Northamptonshire».

An illegitimate child born during World War II, McClean was first placed in a foster home in Dublin and then in Fegan's English orphanage. It was an institution of a kind that no longer exists today: hundreds of boys, all under a private number, biblical classes every day, liquid porridge, physical abuse. He came there as a three-year-old. This was followed by «12 years of constant struggle for survival».

English politician Thomas Fairfax once said: "«I am fighting nature, primitive and rude». I asked McClean if he felt the same way when he was alone with the ocean.

«Fighting the Atlantic? No, that's the wrong approach. You can't fight the forces of nature. You'll end up drowning. You'll end up drowning. Deal with it. Bend with the wind».

Having survived under conditions most people would find unbearable, does he feel special?

«Oh, yes. We're all special. We're all different, and therefore special. It's all about not getting too complacent. I'm pretty cocky myself, though, in a way. Because when someone calls me a smug bastard or tells me I'm a fucking psycho, I feel good. I like it. Go on. I know there are people who admire me for all this, so I'm not crazy».