Silence distinguished this journey from all previous ones. However, some of the sounds were still coming out. The wind was still blowing the sails and howling in the gear. The waves were still splashing against the fiberglass hull. Other sounds were heard, such as the muffled knocking and creaking of the boat's hull hitting the wreckage. All that was missing was the screams of seabirds that accompanied the boat on previous voyages.

There were no birds, because there were no fish.

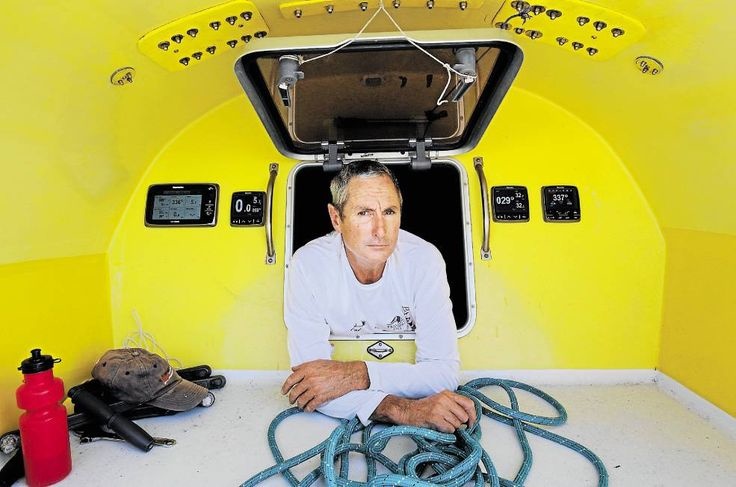

Exactly 10 years ago a yachtsman from Newcastle, Ivan McFadden, was on the same course from Melbourne to Osaka. All he had to do to make a successful catch back then was throw a bait fishing rod.

«In those 28 days of swimming, it wasn't even a day before we caught a good fish that was then cooked with rice for dinner»," McFadden recalled. This time, the catch was limited to just two fish on the long journey.

Not a fish. No birds. Almost no sign of life.

«I've grown accustomed to the birds and their screams over the years," he admits. - They used to accompany the boat, sometimes landing on the mast before soaring into the sky again. Swarms circling far above the sea and hunting for sardines were an everyday sight».

In March and April of this year, however, his boat, the Funnel Web, was surrounded only by the silence and desolation that reigned over the ghostly ocean.

To the north of the equator, above New Guinea, seafarers saw a large fishing boat encircling the reefs in the distance. «All day long, it was trawling back and forth again. The ship was big, like a floating base»," Ivan said. And at night, in the light of spotlights, the ship continued its work. In the morning, McFaddien quickly woke up his partner, saying the ship launched a speedboat.

«No wonder I was concerned. We had no weapons, and pirates in those waters are quite common. I knew if those guys were armed, we were missing," he recalls. "But they weren't pirates, at least not in the conventional sense. A boat moored, and the Melanesian fishermen gave us fruit, jams, and canned food. They also shared five sugar bags full of fish. Fish was good, big, different species. Some were fresh, and some were obviously in the sun for a while. We explained to them that with all the desire not to eat everything. It was just the two of us, and there wasn't much»storage space.

They shrugged their shoulders and offered to throw the fish overboard, saying they would have done the same thing anyway. They explained that it was only a small part of the daily bycatch. All they wanted was tuna, and everything else wasn't good for anything. Fish like that was killed and dumped.

They'd trawl around the reef from morning to night, destroying all life in the way.

McFadden felt something burst in his heart. That ship was only one of countless others who hid behind the horizon and did similar work.

It's

no wonder the sea was dead

. No wonder the bait fishing rod was left without a catch. There was nothing to catch. If it seems depressing, it's worse.

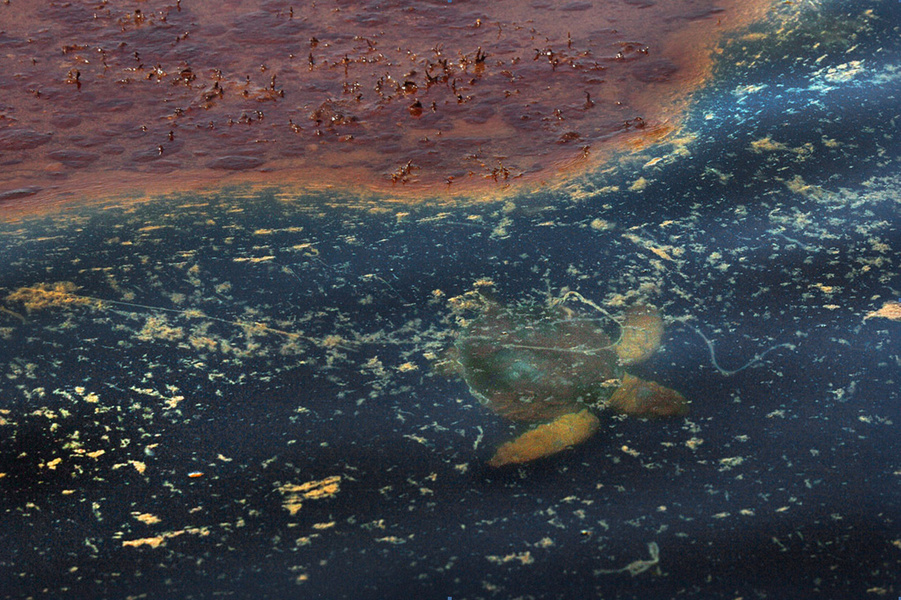

The next route was from Osaka to San Francisco. Almost throughout the voyage, a sense of disgusting horror and fear added to the desolation: «When we left the shores of Japan, it seemed as if the ocean itself had been deprived of life.

We could hardly see anything alive. We met a whale that seemed to be spinning helplessly on the surface of the water, with something on its head that looked like a big tumor.

Pretty disgusting spectacle. In my whole life, I'd fought for miles and miles of ocean space. I'm used to seeing turtles, dolphins, sharks and large flocks of vanity hunting birds. This time for 3,000 nautical miles

,I didn't see a sign of life».

Where life used to be, now there were scary piles of garbage swimming. Some of them were the aftermath of the tsunami that hit Japan a couple of years ago. The wave overwhelmed the coast, picked up an incredible pile of everything and took it back to sea. Everywhere you look, all this garbage is still there.

Glenn, Ivan's brother, came aboard in Hawaii to go to the United States. He was shaken «by countless thousands» of yellow plastic buoys, giant webs of synthetic rope, fishing line and nets.

Millions of pieces of polypenostirol. Solid oil and gasoline film.

Countless hundreds of wooden electric poles uprooted by a deadly wave and soaking their wires in the middle of the sea.

«You used to just start the engine in windless weather," Ivan recalled, "but not anymore. In many places, we couldn't start the motor for fear that it would wrap ropes and wires around a screw. It's an unheard of situation for the open sea. And if we did decide to start the engine, it was not at night and only in the daytime, watching the garbage from the bow of the ship.

North of Hawaii, you could see through the water column from the bow of the ship. I could see that the wreckage and garbage were not only on the surface but also deep in the ocean. They ranged in size from plastic bottles to wrecks the size of a large car or truck. We saw a factory pipe rising above the surface of the water. Under water, something like a boiler was attached to it. We saw something that looked like a container swaying on the waves. We were maneuvering among these wreckage. It was like we were sailing through a dumpster.

We

could always hear the hull bumping into the trash under deck

and we were always afraid to jump into something really big. And so the hull was already covered in dents and scratches from debris and shrapnel we never saw».

Plastic was all over the place. Bottles, bags, all kinds of household rubbish you can imagine, from broken chairs to garbage shovels, toys and kitchen utensils.

There was something else. The ship's bright yellow colour, not faded from the sun or seawater over the years, reacted with something in Japanese waters, losing its luster in a strange and unprecedented way.

Having returned to Newcastle, Ivan McFadden is still trying to recover from the shock. «The ocean is devastated»," he says, shaking his head and hardly believing it himself.

Aware of the magnitude of the problem and that no organization or government seems interested in solving it, McFaddien is looking for a way out. He plans to influence government ministers, hoping to get their help.

The first thing he wants to do is to reach out to the leadership of the Australian Shipping Organization in an effort to engage yacht owners in an international volunteer movement and thus control the garbage and monitor marine life.

McFadden joined the movement while he was in the U.S. in response to a request from U.S. scientists who in turn asked yacht owners to report daily and collect samples for

radiation

samples

, which was a serious problem caused by the tsunami and subsequent accident at a nuclear power plant in Japan.McFadden asked the scientists a question: why not demand that the fleet be sent out to clean up the debris?

But they answered that it was estimated that the damage to the environment from burning fuel at such a clean-up would be

too great.It's easier to keep all garbage in its place.

From The Herald.